By: E.J. Lawrence

My apologies to the reader for the really bad pun in the title. I just couldn’t resist.

I have a very vivid memory from childhood. I was four or five, and I was sitting in the living room of our apartment watching The Little Mermaid on VHS. My dad was on the couch watching with me. I don’t remember how I felt about the movie up until this point, but I do remember the moment that terrified me.

To add some context, I happened to be a pretty adventurous child who wasn’t afraid of much–no monsters in my closet or under my bed. No night terrors or fear of the dark. But the most scared I ever remember being as a small child happened toward the end of The Little Mermaid. It’s the moment when the sea-witch Ursula’s identity is revealed, and suddenly, she begins to grow…and grow…and grow. I remember screaming, “Daddy, turn it off!” as I covered my eyes with my hands. I didn’t watch The Little Mermaid for probably another ten years.

To date, no mythical or fairy tale creature terrifies me quite like the witch. She can steal your voice; your life; your very soul. The Slavic Baba Yaga is particularly fearsome–her house stands on chicken legs. And, well…there’s just something not quite natural about a house that’s stilted on two chicken legs.

Witches. Are. Terrifying.

And yet, one of the little-known (or little emphasized) points about the fairy tale witch is that she’s as likely to help as harm. In a Russian version of Cinderella–“Vasilisa the Fair”–Baba Yaga threatens to eat Vasilisa if she does not do as she’s told; however, Vasilisa does as the old woman requires, and it is through her patience that Baba Yaga helps her to marry the Tsar in the end.

This doesn’t make Baba Yaga good; but it does show how even the witches in these stories have their own codes of honor and are perhaps more nuanced than we often give them credit for.

In Japanese folklore, there’s the Yama Uba who, like Baba Yaga, can be harsh, but will also help a lost traveler or bestow wealth on the needy. I have heard the argument that the witch in “Sleeping Beauty” isn’t all bad–she puts the girl to sleep, after all, rather than kill her. Perhaps even she had a modicum of feeling?

Fairy tale witches–like everything else in a fairy tale–serve more as symbols than independent characters. Though, what they’re symbols for has stirred a great deal of debate.

Some argue that witches are women who represent an independence that society fears; that she is the unbridled power of women.1 Some argue that witches represent the fears of the female protagonist–the part of herself that she represses, but a very real, tangible image of what she has the potential to become.2 Still others say that the witch is a symbol of the negative aspects of femininity–rather than nurture children, she eats them; rather than create healing herbs, she dabbles in poisons and harmful potions.3 Perhaps the fairy tale witch is all of these, or at least a mixture of some.

What I think is interesting to point out when trying to determine the role of the fairy tale witch is the etymology of the word itself. For one, the word is so old that determining its exact etymology is difficult. The OED marks it of “indeterminate origin,” but that doesn’t stop there from being theories. On the one hand, it could be cognate with the words “wicked” and “wicce” (meaning “bad”). On the other, it could be kin to the words “wizard” and “wise”–both words with positive connotations.4 In many early English manuscripts, the word was used interchangeably to refer to a woman who dabbled in dark magic or a woman who used healing herbs to save someone’s life. It seems that the English language has long recognized the nuance and the duality of the term, even if they more often associate the word with the former rather than the latter.

And yet, all of that seems to be consistent with what we know of fairy tale witches themselves. They can be malicious and malevolent, seeking to harm two poor children lost in the woods or poisoning their stepdaughter with a shiny red apple. But they can also be good, helping a young maiden escape her evil stepmother and find love or casting charms of protection when it suits her purposes. But perhaps it is her unpredictability or perceived capriciousness that causes the word “witch” to give us such uneasiness. I can’t say for sure.5

Yet, I can think of no other fairy tale character as nuanced or as complicated as the witch. Even within the confines of the fairy tale universe, she stands apart as independent, making decisions as they come; wielding her skills and talents as she pleases. Whether or not this is a “good” thing, I don’t know.

And, in fact, neither does she.

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/24/witch-symbol-feminist-power-azealia-banks

- http://www.anngadd.co.za/2014/12/fairytales-symbols/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/transcending-the-past/201605/mothers-witches-and-the-power-archetypes

- https://www.dictionary.com/browse/witch?s=t

- I can say, however, that it wasn’t Ursula’s capriciousness that frightened me when I was a child. I’m pretty sure it was her stealing Ariel’s voice and then growing into a giant octopus.

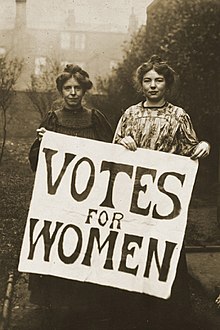

ideology has shifted over time. In the so-called “first wave” of feminism in the nineteenth century, for example, the general focus was on voting rights. During the middle of the twentieth century, many feminists fought for equal pay, while others protested against exploitation. At the transition to the twenty-first century, the focus for several years has included digital activism and collaboration, while other feminists focus on obtaining better representation in politics or family leave in the workplace. Just because someone puts their emphasis on one area of gender-based equity doesn’t mean they’re not “doing” feminism correctly. Many textbooks on the matter pluralize the word “feminism” to emphasize its plurality of meaning.

ideology has shifted over time. In the so-called “first wave” of feminism in the nineteenth century, for example, the general focus was on voting rights. During the middle of the twentieth century, many feminists fought for equal pay, while others protested against exploitation. At the transition to the twenty-first century, the focus for several years has included digital activism and collaboration, while other feminists focus on obtaining better representation in politics or family leave in the workplace. Just because someone puts their emphasis on one area of gender-based equity doesn’t mean they’re not “doing” feminism correctly. Many textbooks on the matter pluralize the word “feminism” to emphasize its plurality of meaning.

pagan movement of modern day), the Bodhi Tree, its very name meaning the awakening or enlightenment of Buddha, and the Tree of Knowledge of the Judaic tradition. In each depiction, there are strong connections to humanity and the human experience. While the divine, or immortal may be connected to the tree, it is often in a human-like capacity that ascends into some type of enlightenment (in the case of monotheism, knowledge that leads to disaster). This can be explained by the idea that the tree is a mirror of humanity itself – ever rooted to the Earth by reaching for something greater, something higher, caught in a state in-between.

pagan movement of modern day), the Bodhi Tree, its very name meaning the awakening or enlightenment of Buddha, and the Tree of Knowledge of the Judaic tradition. In each depiction, there are strong connections to humanity and the human experience. While the divine, or immortal may be connected to the tree, it is often in a human-like capacity that ascends into some type of enlightenment (in the case of monotheism, knowledge that leads to disaster). This can be explained by the idea that the tree is a mirror of humanity itself – ever rooted to the Earth by reaching for something greater, something higher, caught in a state in-between. repetitive in Western culture. I’d like to examine these through the lens of the Greek myth of Daphne, the nymph lustfully pursued by Apollo until she is transformed into the laurel tree in order to escape. It is a timely myth to revisit for the modern audience, as many women via the Me Too movement have spoken out against male sexual misconduct, particularly from powerful men. It has spurred not only conversations on the sexual harassment, pressure and assault on women, but questions concerning sex and power dynamics.

repetitive in Western culture. I’d like to examine these through the lens of the Greek myth of Daphne, the nymph lustfully pursued by Apollo until she is transformed into the laurel tree in order to escape. It is a timely myth to revisit for the modern audience, as many women via the Me Too movement have spoken out against male sexual misconduct, particularly from powerful men. It has spurred not only conversations on the sexual harassment, pressure and assault on women, but questions concerning sex and power dynamics. greater, a life-threatening or ruining possibility.

greater, a life-threatening or ruining possibility. Daphne is described as athletic and when she flees, she gives a difficult pursuit for Apollo. But he is ultimately a god, so he is able to gain ground on her. Despite Daphne’s abilities, she cannot escape Apollo’s will. We could read this as despite female abilities and potential, women cannot escape society’s will.

Daphne is described as athletic and when she flees, she gives a difficult pursuit for Apollo. But he is ultimately a god, so he is able to gain ground on her. Despite Daphne’s abilities, she cannot escape Apollo’s will. We could read this as despite female abilities and potential, women cannot escape society’s will.

the withdrawal of God’s protection. In Celtic culture, trees, or a grove can serve as a gateway to the realm of the faery, a mysterious world of amazement and entrapment, rife with equal parts wonder and danger. Such transformations and withdrawal from societal cooperation are by nature threatening to that society, but there is a freedom that can be found.

the withdrawal of God’s protection. In Celtic culture, trees, or a grove can serve as a gateway to the realm of the faery, a mysterious world of amazement and entrapment, rife with equal parts wonder and danger. Such transformations and withdrawal from societal cooperation are by nature threatening to that society, but there is a freedom that can be found. I met a lady in the meads,

I met a lady in the meads, warning to men of what could happen if women were allowed such self-direction. Indeed it hints at the very destruction of male power structures, “…pale kings and princes too, pale warriors, death-pale were they all.”

warning to men of what could happen if women were allowed such self-direction. Indeed it hints at the very destruction of male power structures, “…pale kings and princes too, pale warriors, death-pale were they all.”

received such harsh reviews for The Awakening. Such negativity would have been enough to permanently discourage someone from trying to publish anything again, especially since that novel conveys such pure openness at the expense of risking reputation. But now the novel that was considered obscene and received scathing criticism is considered one of the most important works in literature, especially feminist literature.

received such harsh reviews for The Awakening. Such negativity would have been enough to permanently discourage someone from trying to publish anything again, especially since that novel conveys such pure openness at the expense of risking reputation. But now the novel that was considered obscene and received scathing criticism is considered one of the most important works in literature, especially feminist literature.