The theme of “On Stage” takes a darker turn this week as I expand into film. The Limehouse Golem is a 2016 film adapted by screenwriter Jane Goldman and based on Peter Ackroyd’s 1994 novel Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem, which was also published as The Trial of Elizabeth Cree. I can’t talk about it without giving away secrets, so be aware that spoilers abound!

The story opens with Elizabeth Cree (portrayed by Olivia Cooke in the movie), “Little Lizzie” as she’s known in the stage circles, being accused of poisoning her husband, John, a reporter and playwright, based on the evidence that she prepared his nightly draught, which was laced with poison.

The story opens with Elizabeth Cree (portrayed by Olivia Cooke in the movie), “Little Lizzie” as she’s known in the stage circles, being accused of poisoning her husband, John, a reporter and playwright, based on the evidence that she prepared his nightly draught, which was laced with poison.

In the midst of Lizzie’s trial, Inspector Kildare (Bill Nighy) gets handed the nigh-unsolvable case of the Limehouse Golem, a series of seemingly random and unconnected murders in the Limehouse district of London. The clues lead him to a journal, ostensibly written by the Golem, and Kildare latches upon John Cree as the number-one suspect. He believes if he proves that Cree was the Golem, Lizzie could argue that he committed suicide because of his crimes and the charges against Lizzie could be dropped.

To untangle the mystery, we have to learn more about Lizzie’s life. She grows up in poverty with an abusive mother whose work brings Lizzie into the path of abusive men. Once she escapes that situation, she finds herself in the realm of Dan Leno, a real-life historical figure known for performing female roles in drag. Of Leno, Lizzie says, “He portrays the suffering of women. My gender becomes inured to injustice. We expect it until we can greet it merely with a shrug…. The line between comedy and tragedy is a fine one.” In one scene, we see Leno singing a song as an abused wife. He pulls out a knife and sings, “He blacked both my eyes without warning, but I’ll be waiting for him tonight.”

Dan Leno’s career paves the way in the story for Golem’s journal, which features multiple passages referring to murder as “pantomime in its purest form.” About the first murder, the Golem writes, “But I was a beginner, an understudy, not yet ready to take the stage. An artist must perfect his craft, and tonight I would start with a small, private rehearsal,” by which the Golem means—kill a prostitute. One entry says, “[The victim] was a player waiting for a role. Of course, I obliged her. The public yearned for the next installment, and one should never keep an audience waiting.” Another says, “Ratcliff Highway was a tour de force,” referring to two multiple-victim murders committed by John Williams in 1811. In a macabre sort of homage, the Golem performs murders at the same location, and “as an actor may take home a program as a souvenir, so I returned with a blood-soaked shawl belonging to the clothes seller’s wife.”

As the Golem is terrorizing Limehouse, Lizzie finds acclaim and acceptance on the stage of the music hall, but there’s only so far she can go. As a woman, she’ll never be taken seriously as an actor. “We’re clowns, Dan,” she says to Leno. “We’ll be forgotten.” As Kildare recognizes and points out, she doesn’t want to be saved “by any man.” During one of their interviews while Lizzie is in prison awaiting her sentencing, she says, “What I deserve is to live freely and in death be remembered for my accomplishments, not as the wife who poisoned her husband, my name forever tethered to his.”

If you haven’t guessed by now (and I certainly didn’t my first time watching the film), here is the big twist of the story—Lizzie is the Golem. Early in the trial, she says, “My husband was adept at presenting a false face to the world.” The prosecuting lawyer responds, “And that is something you would understand, is it not, Mrs. Cree? Playing a role?” It’s not until the story’s final reveal that we understand how true this statement is—and not simply because of her life on the stage. In every meeting with him as he attempts to save her, Lizzie plays a role for Kildare. In fact, she never stops playing a role—that of the ingénue, a woman whom men are drawn to protect, only to realize she neither wants nor needs protection.

Instead, what she wants is lasting fame. She continues to discuss her case with Kildare because she appoints him as the keeper of her story. This will make his career, and her career will make her infamous. When he finalizes realizes this, he denies her last wish by letting her hang for John’s murder and by burning the written confession that she—not her husband—is the Golem.

Lizzie cannot achieve power as a woman, as her true self, even though she performs as a man on stage. Instead, she seeks that power by creating and performing the role of the Golem, whom everyone assumes is a man. In a ghoulish and awful way, she proves herself to everyone who underestimated her and her gender. As she murders one man, she even says, “Oh, I know, I know. Few would think a woman capable of such artistry.” And while I find myself appalled at her lack of remorse and can’t condone her crimes, such a character—one who so readily blurs the line between stage performance and reality—certainly makes for an exciting story.

All quotes from The Limehouse Golem. Director: Juan Carlos Medina. Screenwriter: Jane Goldman. Based on the novel Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem by Peter Ackroyd.

Featured image: Bill Nighy as Inspector Kildare and Olivia Cooke as Lizzie Cree in The Limehouse Golem. http://www.imdb.com.

To break down the old Norse Valkyrjur, Valr referred to the slain of the battlefield and kjósa, meant ‘to choose.’ Valkyrie translated to ‘Choosers of the Slain,’ a title that not only encompassed their choice of which warriors were granted Valhalla status, but who would die in battle. Valkyries didn’t shy away from invoking some heavy-duty black magics to ensure their choices came to fruition. In Njal’s Saga, there is an instance of twelve Valkyrie gathered around a loom, weaving fate like the Norns, though their materials are far grimmer. Here, the Valkyrie use intestines for thread, severed heads for weights, and swords and arrows for beaters, while they gleefully chant their hit list. The Saga of the Volsungs compares the sight of a Valkyrie to ‘staring into an open flame.’ To the Anglo-Saxons, they were spirits of carnage.

To break down the old Norse Valkyrjur, Valr referred to the slain of the battlefield and kjósa, meant ‘to choose.’ Valkyrie translated to ‘Choosers of the Slain,’ a title that not only encompassed their choice of which warriors were granted Valhalla status, but who would die in battle. Valkyries didn’t shy away from invoking some heavy-duty black magics to ensure their choices came to fruition. In Njal’s Saga, there is an instance of twelve Valkyrie gathered around a loom, weaving fate like the Norns, though their materials are far grimmer. Here, the Valkyrie use intestines for thread, severed heads for weights, and swords and arrows for beaters, while they gleefully chant their hit list. The Saga of the Volsungs compares the sight of a Valkyrie to ‘staring into an open flame.’ To the Anglo-Saxons, they were spirits of carnage.

That’s one of the reasons I was attracted to Ragnarök Unwound, written by Kristin Jacques, author of Zombies Vs. Aliens and the upcoming Marrow Charm from Parliament House Press. Ragnarök Unwound is the story of Ikepela Ives, who is known as the Fate Cipher. The Fate Cipher’s job is to untangle the threads of fate. The only problem is Ives is the first part-mortal Cipher, and no one ever taught her how to use her powers. She runs away from her duty until one day, she can’t anymore. A Valkyrie locates her in a bar and pleads for her help in stopping Ragnarök, which has been set in motion. Jacques blends Norse and Hawaiian mythology for a truly unique tale filled with a unique ensemble cast.

That’s one of the reasons I was attracted to Ragnarök Unwound, written by Kristin Jacques, author of Zombies Vs. Aliens and the upcoming Marrow Charm from Parliament House Press. Ragnarök Unwound is the story of Ikepela Ives, who is known as the Fate Cipher. The Fate Cipher’s job is to untangle the threads of fate. The only problem is Ives is the first part-mortal Cipher, and no one ever taught her how to use her powers. She runs away from her duty until one day, she can’t anymore. A Valkyrie locates her in a bar and pleads for her help in stopping Ragnarök, which has been set in motion. Jacques blends Norse and Hawaiian mythology for a truly unique tale filled with a unique ensemble cast.

Counter Reformation. For a society dominated by the rules of Catholic Christianity for centuries, the threat of Protestantism was just as threatening to the social structure as it was the spiritual. Witches in Catholic regions were accused of fouling the Eucharist or using it for spells. Protestant regions were much more susceptible to this phenomenon. This may be due to the intense need to differentiate themselves from the Catholic Church as beacons of righteousness and in doing so, validate their emerging social structures. This opened the possibility for many ideas and it is no wonder that female agency was particularly suppressed during this transition.

Counter Reformation. For a society dominated by the rules of Catholic Christianity for centuries, the threat of Protestantism was just as threatening to the social structure as it was the spiritual. Witches in Catholic regions were accused of fouling the Eucharist or using it for spells. Protestant regions were much more susceptible to this phenomenon. This may be due to the intense need to differentiate themselves from the Catholic Church as beacons of righteousness and in doing so, validate their emerging social structures. This opened the possibility for many ideas and it is no wonder that female agency was particularly suppressed during this transition.

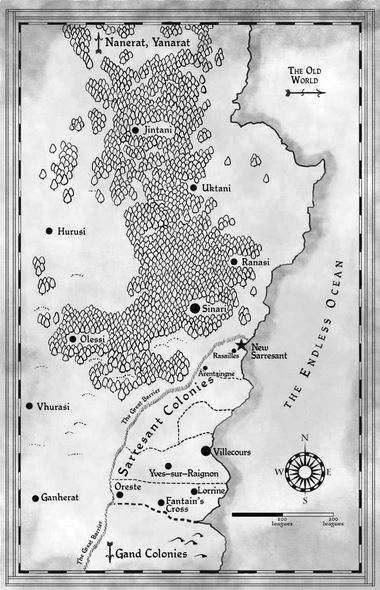

All of that is to explain why this month, I had to get a little creative when it came to keeping with the theme. I’m going to look at Soul of the World, the first book in the Ascension Cycle, an epic fantasy series by David Mealing. The world is inspired by the European settlement of North America. On the coastline are the colonies of Sarresant, including the capital city of New Sarresant, whose culture is reminiscent of France. To the south are the colonies of Gand, reminiscent of England. To the west of the colonies is the Great Barrier, which separates them from tribes indigenous to the land, among them the Sinari, from which one of the protagonist hails.

All of that is to explain why this month, I had to get a little creative when it came to keeping with the theme. I’m going to look at Soul of the World, the first book in the Ascension Cycle, an epic fantasy series by David Mealing. The world is inspired by the European settlement of North America. On the coastline are the colonies of Sarresant, including the capital city of New Sarresant, whose culture is reminiscent of France. To the south are the colonies of Gand, reminiscent of England. To the west of the colonies is the Great Barrier, which separates them from tribes indigenous to the land, among them the Sinari, from which one of the protagonist hails.

The passivity of Ophelia’s death coupled with later statements in the play that suggest it was far from an accident leave us with ambiguity. Did she fall, as Gertrude suggests, and was not in her right mind enough to save herself or even, in fact, realize the danger she was in? Or, as a gravedigger suggests, did she see death as the only way to escape the cage the men in her life had created for her? Either way, her drowning instills discomfort, one Klein attempts to lessen by having her escape it entirely. With her knowledge of herbs and medicines as well as help from Horatio and even Gertrude, she’s able to fake her own death and restart her life in a convent. Though she knows no one outside Elsinore, she can’t get any more alone than she was in the castle. By paying attention to her when no one else does, Klein portrays an Ophelia who is “the author of [her] tale, not merely a player in Hamlet’s drama or a pawn in Claudius’s deadly game.”

The passivity of Ophelia’s death coupled with later statements in the play that suggest it was far from an accident leave us with ambiguity. Did she fall, as Gertrude suggests, and was not in her right mind enough to save herself or even, in fact, realize the danger she was in? Or, as a gravedigger suggests, did she see death as the only way to escape the cage the men in her life had created for her? Either way, her drowning instills discomfort, one Klein attempts to lessen by having her escape it entirely. With her knowledge of herbs and medicines as well as help from Horatio and even Gertrude, she’s able to fake her own death and restart her life in a convent. Though she knows no one outside Elsinore, she can’t get any more alone than she was in the castle. By paying attention to her when no one else does, Klein portrays an Ophelia who is “the author of [her] tale, not merely a player in Hamlet’s drama or a pawn in Claudius’s deadly game.”

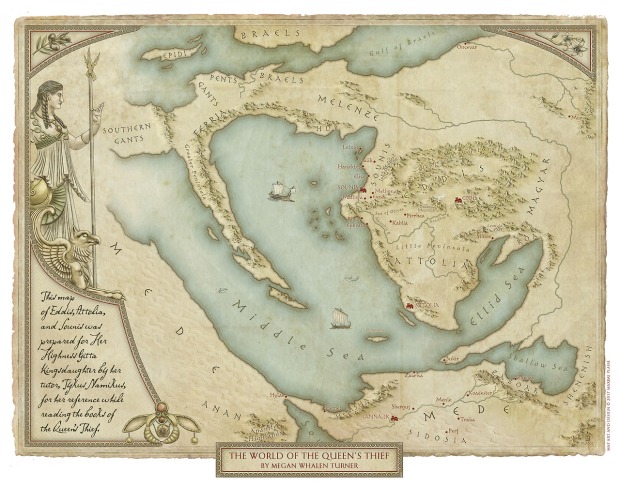

“Standing in the light, surrounded by the dark beyond the lanterns, she seemed lit by the aura of the gods. Her hair was black and held away from her face by an imitation of the woven gold band of Hephestia. Her robe was draped like a peplos, made from embroidered red velvet. She was as tall as the magus, and she was more beautiful than any woman I have ever seen. Everything about her brought to mind the old religion, and I knew that the resemblance was deliberate, intended to remind her subjects that as Hephestia ruled uncontested among the gods, this woman ruled Attolia.” [1]

“Standing in the light, surrounded by the dark beyond the lanterns, she seemed lit by the aura of the gods. Her hair was black and held away from her face by an imitation of the woven gold band of Hephestia. Her robe was draped like a peplos, made from embroidered red velvet. She was as tall as the magus, and she was more beautiful than any woman I have ever seen. Everything about her brought to mind the old religion, and I knew that the resemblance was deliberate, intended to remind her subjects that as Hephestia ruled uncontested among the gods, this woman ruled Attolia.” [1] but perhaps she was never given the chance to be.

but perhaps she was never given the chance to be.