By: E.J. Lawrence

I am currently in the middle of teaching my Shakespeare unit to my students. I suppose that’s why, when the theme of female friendship came up this month, I immediately thought of Rosalind and Celia from Shakespeare’s As You Like It. While this isn’t a play I’ve ever taught before, it is one of my favorites, and one of the reasons I love it so much is because of the beautiful depiction of friendship between these two women.

In this play, Rosalind is a young woman whose father is out of favor with his brother, the treacherous duke–and he is thus exiled–but Celia, the duke’s daughter, so loves her friend that she begs Rosalind be allowed to stay. The duke dotes on his daughter and cannot deny her this request…until he, for no real reason other than mad jealousy, rescinds his offer and tells Rosalind she must leave immediately, on pain of death. Celia tries to beg for her friend and cousin’s life again, but this time, is denied. Rather than stay at home and mourn for her lost companion, Celia chooses to run away with Rosalind, and the two girls escape to the forest where they meet a shepherd, a band of merry men, and their eventual love interests.

When we first meet Rosalind and Celia, Celia is trying to cheer up Rosalind because of her father’s exile. Though Rosalind is initially reticent, the two end that portion of their conversation with an exchange of witty repartee. The wordplay shows both women to be intelligent and quick, treating conversation like a skill they’ve both sharpened on each other for years. It’s a game they enjoy and are both good at, so it makes for not only comedic dialogue, but also shows that the two friends “get” each other. They even often conspire to “outfool the fool” when they make jokes at Touchstone’s (“the fool’s”) expense. While they’re talking about whether Fortune and Nature work together or not, Touchstone enters, and their course of conversation turns to make fun at his expense:

CELIA

No? when Nature hath made a fair creature, may she

not by Fortune fall into the fire? Though Nature

hath given us wit to flout at Fortune, hath not

Fortune sent in this fool to cut off the argument?ROSALIND

Indeed, there is Fortune too hard for Nature, when

Fortune makes Nature’s natural the cutter-off of

Nature’s wit.CELIA

Peradventure this is not Fortune’s work neither, but

Nature’s; who perceiveth our natural wits too dull

to reason of such goddesses and hath sent this

natural for our whetstone; for always the dulness of

the fool is the whetstone of the wits. How now,

wit! whither wander you?1

This joke, which is essentially saying that fools exist to be made fun of, and that must be why Touchstone has arrived, has built for several lines. Such a joke requires the skill and teamwork of two people who have known each other for some time, and thus know how to set each other up for a punchline. We all have someone with whom we share jokes–inside jokes, puns, etc. These “shared” jokes are usually only between those with whom we share more than just jokes. Witty back-and-forths require a connection, and inside jokes–like the one here between Celia and Rosalind–require an “inner circle” connection. We don’t often joke around in this manner with someone we aren’t close to, and we certainly don’t expect mere acquaintances or “friends of circumstances” to deliver when we set them up for a punchline. These two have a friendship built on common intellect, yes, but also on years of close communication.

It’s more than just their sense of humor that cements them as friends. It’s also their willingness to walk through fire for one another. When Rosalind is banished by Celia’s father, she declares she is now alone. Celia responds: “Rosalind lacks then the love/ Which teacheth thee that thou and I am one:/ Shall we be sunder’d? shall we part, sweet girl?/ No: let my father seek another heir.”2 Celia is not banished; she isn’t the one who must leave. She could have provided her friend with some supplies and sent her on her way, choosing to continue her life in comfort. Instead, she dons the clothes of a peasant girl and runs with her cousin into the forest, giving up every scrap of wealth and comfort she had to give her closest companion some comfort.

To me, that’s the greatest depiction of friendship there is. John 15:13 says, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”3 That, essentially, is what Celia does for Rosalind. She risks death and physical discomfort for her closest companion.

Once in the forest, Rosalind disguises herself as a man and Celia disguises herself as a peasant, and the two women conceal each other’s identities as they find mischief, mayhem, love, and family in the forest. In the end, in true comedic fashion, everything works out for both women–mostly thanks to Rosalind’s quick-thinking and Celia’s careful protection of her friend’s identity. And while, for me, the play holds many great moments (Jacques’ speeches speak to my soul…which should probably alarm me), my favorite part has always been the beautiful friendship between Celia and Rosalind–their matched wits, their compassion, and the way they protect and look out for each other in the darkest of circumstances.

- Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Act I.Scene 2, http://shakespeare.mit.edu/asyoulikeit/full.html

- —. As You Like It. Act I. Scene 2, http://shakespeare.mit.edu/asyoulikeit/full.html

- The Bible, King James Version, Bible Gateway, https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+15%3A13&version=KJV

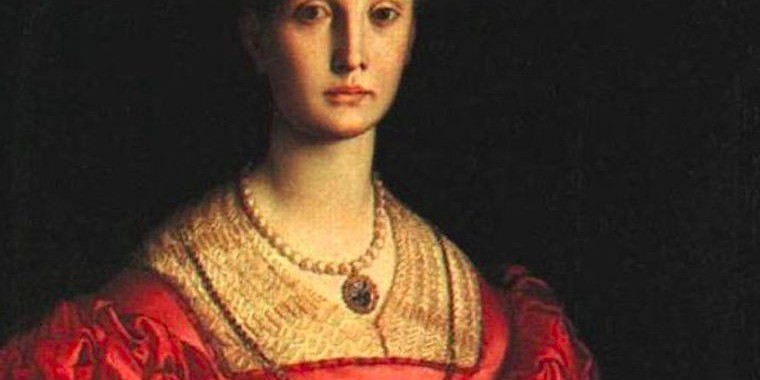

- Featured Picture: “Rosalind and Celia” (1909)

few times have we seen a female one. We didn’t know what to expect. There was a nationwide gasp when the beautiful Theron transformed herself into the physicality of Wuornos through the help of make-up, but also through something more, a dark vulnerability.

few times have we seen a female one. We didn’t know what to expect. There was a nationwide gasp when the beautiful Theron transformed herself into the physicality of Wuornos through the help of make-up, but also through something more, a dark vulnerability.

members, but there is no definitive evidence to prove them. She married young to Ferenc Nàdasdy. Shortly before at age thirteen, she gave birth to a child most likely fathered by a male of a lower social class, possibly even a servant. It is no surprise that the child was sent away immediately after birth. Bathory was considered a beauty in her time and following the birth of her first child, got into line with social expectations and often capitalizing on them. If anything, she seemed to become acutely aware of appearances.

members, but there is no definitive evidence to prove them. She married young to Ferenc Nàdasdy. Shortly before at age thirteen, she gave birth to a child most likely fathered by a male of a lower social class, possibly even a servant. It is no surprise that the child was sent away immediately after birth. Bathory was considered a beauty in her time and following the birth of her first child, got into line with social expectations and often capitalizing on them. If anything, she seemed to become acutely aware of appearances.

about her is quite a story unto itself, but she’s become more than just that. She’s a figure of compassion, tragedy and encapsulates the destruction of the Native American peoples’ way of life at the hands of the Europeans. Pocahontas remains a noble figure even in the face of violence and hatred. Somehow she remains personally, above the fray. Her history is obscured by time, but the mythology of the part she played is simultaneously romantic, poetic yet voiceless. There is never a moment in the records that we “hear” Pocahontas speak. But she plays a big role in the awareness of two prominent colonists, John Smith and John Rolfe.

about her is quite a story unto itself, but she’s become more than just that. She’s a figure of compassion, tragedy and encapsulates the destruction of the Native American peoples’ way of life at the hands of the Europeans. Pocahontas remains a noble figure even in the face of violence and hatred. Somehow she remains personally, above the fray. Her history is obscured by time, but the mythology of the part she played is simultaneously romantic, poetic yet voiceless. There is never a moment in the records that we “hear” Pocahontas speak. But she plays a big role in the awareness of two prominent colonists, John Smith and John Rolfe. dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death.”

dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death.” disbelief over the Englishmen’s folly. While the relationship between the settlers and the Powhatans were shaky at best, Pocahontas, young and representing her people arrived with life saving food. She was the face of possibility between the two cultures. There were attempts to garner positive relationships. These often failed, mostly through cultural misunderstandings, external pressures and pure aggression. Nonetheless, Pocahontas was painted as a figure that stood outside of all this. Her gifts of food were seen as acts of kindness.

disbelief over the Englishmen’s folly. While the relationship between the settlers and the Powhatans were shaky at best, Pocahontas, young and representing her people arrived with life saving food. She was the face of possibility between the two cultures. There were attempts to garner positive relationships. These often failed, mostly through cultural misunderstandings, external pressures and pure aggression. Nonetheless, Pocahontas was painted as a figure that stood outside of all this. Her gifts of food were seen as acts of kindness. father as well as weapons, her previous kindness was easily forgotten. However, her father the Chief was not interested in a trade of any kind. So Pocahontas remained with the settlers, eventually becoming Christian, adopting an English name (Rebecca), marrying and having a son with the widower John Rolfe.

father as well as weapons, her previous kindness was easily forgotten. However, her father the Chief was not interested in a trade of any kind. So Pocahontas remained with the settlers, eventually becoming Christian, adopting an English name (Rebecca), marrying and having a son with the widower John Rolfe.

notwithstanding, Marguerite de Navarre was the archetypal “Renaissance Man.” Though born at a time when even the most talented women were unlikely to be recognized for their artistic and intellectual contributions, history remembers her not only for her hereditary place in the history of European royalty, but for her art, and for the support and protection that she provided for some of the great other great thinkers and artists of the Renaissance.

notwithstanding, Marguerite de Navarre was the archetypal “Renaissance Man.” Though born at a time when even the most talented women were unlikely to be recognized for their artistic and intellectual contributions, history remembers her not only for her hereditary place in the history of European royalty, but for her art, and for the support and protection that she provided for some of the great other great thinkers and artists of the Renaissance. Historically speaking, she dodged a bullet when negotiations failed that would have her marry England’s Prince of Wales, who would go on to rule as King (and serial wife-decapitator) Henry VIII. Instead, she was married to the Duke of Alençon, who was captured (along with her brother Francis I, and future husband Henry II of Navarre) during the French debacle at the battle of Pavia in 1525 and died not long after. According to accounts Marguerite, a notable diplomat in her own right, rode day and night into Spanish territory to secure her brother’s release.

Historically speaking, she dodged a bullet when negotiations failed that would have her marry England’s Prince of Wales, who would go on to rule as King (and serial wife-decapitator) Henry VIII. Instead, she was married to the Duke of Alençon, who was captured (along with her brother Francis I, and future husband Henry II of Navarre) during the French debacle at the battle of Pavia in 1525 and died not long after. According to accounts Marguerite, a notable diplomat in her own right, rode day and night into Spanish territory to secure her brother’s release. Though her first marriage was childless, Marguerite’s lone surviving child would go on to cement important place in history. Her daughter Jeanne III was an important figure in the Huguenot movement, and the mother of Henry IV of France, the first of the Bourbon line of French kings. The loss of her only son as an infant is often suggested to be the inspiration for her controversial poem Miroir de l’âme pécheresse (“The Mirror of the Sinful Soul”), a devotional and personal work that caused outrage in some religious circles.

Though her first marriage was childless, Marguerite’s lone surviving child would go on to cement important place in history. Her daughter Jeanne III was an important figure in the Huguenot movement, and the mother of Henry IV of France, the first of the Bourbon line of French kings. The loss of her only son as an infant is often suggested to be the inspiration for her controversial poem Miroir de l’âme pécheresse (“The Mirror of the Sinful Soul”), a devotional and personal work that caused outrage in some religious circles. the development of countless Renaissance artists, she did so while somehow maintaining her own reputation in her own era. History is littered with woman of talent and drive who succeeded only in retrospect, who are appreciated only posthumously for their contributions, and in their own time ignored or even scored for the audacity to aspire to “men’s work.” Marguerite was a unique artifact of history; she was the personal embodiment of arts and intellectual endeavors, who perfectly reflected the changing face of Western society. Her direct and indirect contributions to the arts, religious discourse, and humanist thought earn her a well-deserved reputation as the first “modern woman,” and heralded the rise of women authors and scholars that came after her.

the development of countless Renaissance artists, she did so while somehow maintaining her own reputation in her own era. History is littered with woman of talent and drive who succeeded only in retrospect, who are appreciated only posthumously for their contributions, and in their own time ignored or even scored for the audacity to aspire to “men’s work.” Marguerite was a unique artifact of history; she was the personal embodiment of arts and intellectual endeavors, who perfectly reflected the changing face of Western society. Her direct and indirect contributions to the arts, religious discourse, and humanist thought earn her a well-deserved reputation as the first “modern woman,” and heralded the rise of women authors and scholars that came after her.

through rose colored lenses. It’s hard to picture such a heavy focus on beauty before the makeup industry came along (an industry I’ve known and felt forced to be subservient to for my entire life). People often hold up the art of the renaissance as a time where women were not shamed for their bodies. The women in the paintings look real, are modeled after real women, are unaltered by photoshop or airbrush. But the renaissance was running its course at the same time of Bathory’s vicious murders. Maybe being held up to the impossible standards of goddesses and angels wore women down long before film, magazines, models, and porn ever worked their way into the main thread of society.

through rose colored lenses. It’s hard to picture such a heavy focus on beauty before the makeup industry came along (an industry I’ve known and felt forced to be subservient to for my entire life). People often hold up the art of the renaissance as a time where women were not shamed for their bodies. The women in the paintings look real, are modeled after real women, are unaltered by photoshop or airbrush. But the renaissance was running its course at the same time of Bathory’s vicious murders. Maybe being held up to the impossible standards of goddesses and angels wore women down long before film, magazines, models, and porn ever worked their way into the main thread of society. Who are you trying to look good for? She’s asking for it. Too little makeup is off putting, because the natural face is not what “natural” looks like in magazines and film. You look tired. Are you feeling well?

Who are you trying to look good for? She’s asking for it. Too little makeup is off putting, because the natural face is not what “natural” looks like in magazines and film. You look tired. Are you feeling well? woman attached to you? “But she’s got to be young and beautiful.” And how can girls grow into women who love themselves when they grow up hearing their mothers call themselves fat and ugly? When nearly every representation of a beautiful woman is one that is photoshopped?

woman attached to you? “But she’s got to be young and beautiful.” And how can girls grow into women who love themselves when they grow up hearing their mothers call themselves fat and ugly? When nearly every representation of a beautiful woman is one that is photoshopped?

Once part of the dominant ruling culture of the region, Morisco’s came to occupy a peripheral existence that inspired an excess of suspicion and hostility from Castilian Catholics. The suspicion was not entirely unfounded. Within the home, Morisco mothers continued to teach traditions as well as the Arabic language. Publicly, the adherence to Christian practices took the place of Muslim worship, but not necessarily within the home. But this activity came with great risk. Under the culture of the Inquisition, Moriscos who were found to practice Islam were questioned, usually under torture and executed. It went beyond mere religion, reading and writing in Arabic and later donning traditional Morisco clothing could result in execution. By the mid-16th century, Morisco society could only exist in increasingly smaller confines. The dwindling space had occurred slowly with the erosion of the Caliphate. It was a reflection of the very space of an empire turned kingdom, then eaten up by Christendom until it no longer existed at all. Even before the completion of the Reconquista, the sense of Moorish loss resounded in the formerly great Caliphate as a harbinger of Morisco fate.

Once part of the dominant ruling culture of the region, Morisco’s came to occupy a peripheral existence that inspired an excess of suspicion and hostility from Castilian Catholics. The suspicion was not entirely unfounded. Within the home, Morisco mothers continued to teach traditions as well as the Arabic language. Publicly, the adherence to Christian practices took the place of Muslim worship, but not necessarily within the home. But this activity came with great risk. Under the culture of the Inquisition, Moriscos who were found to practice Islam were questioned, usually under torture and executed. It went beyond mere religion, reading and writing in Arabic and later donning traditional Morisco clothing could result in execution. By the mid-16th century, Morisco society could only exist in increasingly smaller confines. The dwindling space had occurred slowly with the erosion of the Caliphate. It was a reflection of the very space of an empire turned kingdom, then eaten up by Christendom until it no longer existed at all. Even before the completion of the Reconquista, the sense of Moorish loss resounded in the formerly great Caliphate as a harbinger of Morisco fate.