By Kristin Jacques, author of Ragnarök Unwound, forthcoming from Sky Forest Press

The Valkyrie has made a comeback in a big way. While this Norse mythological figure has cropped up from time to time in the modern era, the influx and influence of mythology in recent media has lifted the Valkyrie in a new direction. There is now an abundance of depictions in comic books, novels, television shows and blockbuster films, where the Valkyrie has become synonymous with the B.A.M. (Bad Ass Motha), the tough-as-nails female heroine. This archetypal heroine is a cornerstone in several genres, such as Urban Fantasy.

This representation is not a far cry from their Norse origins, though newer incarnations present a somewhat sanitized version of the original myth, focusing on the noble characteristics of these female extensions of the All Father. The hint of their dark origins is in the etymology of their name.

To break down the old Norse Valkyrjur, Valr referred to the slain of the battlefield and kjósa, meant ‘to choose.’ Valkyrie translated to ‘Choosers of the Slain,’ a title that not only encompassed their choice of which warriors were granted Valhalla status, but who would die in battle. Valkyries didn’t shy away from invoking some heavy-duty black magics to ensure their choices came to fruition. In Njal’s Saga, there is an instance of twelve Valkyrie gathered around a loom, weaving fate like the Norns, though their materials are far grimmer. Here, the Valkyrie use intestines for thread, severed heads for weights, and swords and arrows for beaters, while they gleefully chant their hit list. The Saga of the Volsungs compares the sight of a Valkyrie to ‘staring into an open flame.’ To the Anglo-Saxons, they were spirits of carnage.

To break down the old Norse Valkyrjur, Valr referred to the slain of the battlefield and kjósa, meant ‘to choose.’ Valkyrie translated to ‘Choosers of the Slain,’ a title that not only encompassed their choice of which warriors were granted Valhalla status, but who would die in battle. Valkyries didn’t shy away from invoking some heavy-duty black magics to ensure their choices came to fruition. In Njal’s Saga, there is an instance of twelve Valkyrie gathered around a loom, weaving fate like the Norns, though their materials are far grimmer. Here, the Valkyrie use intestines for thread, severed heads for weights, and swords and arrows for beaters, while they gleefully chant their hit list. The Saga of the Volsungs compares the sight of a Valkyrie to ‘staring into an open flame.’ To the Anglo-Saxons, they were spirits of carnage.

At some point the representation shifted from ‘warrior’ to ‘shield maiden,’ and there, a fine distinction began to surface. Valkyrie served as projections, parts of a greater whole. The Valkyrie were an extension of Odin, but as the focus shifted to their nobler deeds, so too did their autonomy expand. Odin might dictate their choice of who died in battle, but the Valkyrie, such as Brunhild or Sigrun, chose their lovers. They chose mortals to favor and protect. They became susceptible to the vices and failings of mortals, just like other Norse deities. They became more human.

It was this association with fairness, brightness, gold, and bloodshed that has resurfaced in depictions of the modern Valkyrie. There has also been a bit of an amputation from the All Father. A single Valkyrie is a B.A.M., but she comes with a sisterhood. Recent Valkyrie representations include everything from Tessa Thompson’s very memorable kick-butt turn as Marvel’s Valkyrie in the third Thor outing to Rachel Skarsten’s Tamsin in the fantasy femme fatale brawl that is Lost Girl. [pictured: Tessa Thompson as Valkyrie in Marvel’s Thor: Ragnarok.]

In Marvel’s hot take, the Valkyrie were an elite band of female warriors who served in Odin’s army, with Thompson’s character adrift and rudderless without her sisters. (Slight spoiler: she comes back swinging.) Here at least Odin is present, but the Valkyrie, particularly Thompson, have complete autonomy over themselves.

The Valkyrie in the Canadian fantasy drama Lost Girl give a fair nod to their dark origins. Here, the Valkyrie don’t answer to Odin at all, but to Freyja. They still have the soul-taker gig, but with a twist. The Valkyrie consider one another sisters, and they fight like sisters, though the hair is off-limits.

For my own depiction of Valkyrie in Ragnarök Unwound, I draw on the more bombastic qualities present in the myths and modern incarnations in the creation of Hildr—fierce, loyal, and quite literal. Isolated from her sisters, Hildr builds a new sisterhood with the other female characters of the novel to fight the good fight.

A common factor in these modern depictions is while the Valkyrie are singularly B.A.M., the Sisterhood is a force of nature. They draw strength from one another and in turn give their strength to one another.

This mentality of sisterhood carries over into women’s culture. We all want to be Wonder Woman. We want to be the B.A.M., but we are strongest when we lift each other. We raise our sisters on our shields. No matter the depiction, the world they inhabit, or who their boss is, Valkyrie are the Sisterhood of the Fierce.

Sources:

The Saga of the Volsungs

The Viking Spirit by Daniel McCoy

Norse-mythology.org

Lost Girl

Thor: Ragnarok

Featured image: Arthur Rackham, “Wagner’s Ring Cycle: The Valkyrie,” 1910

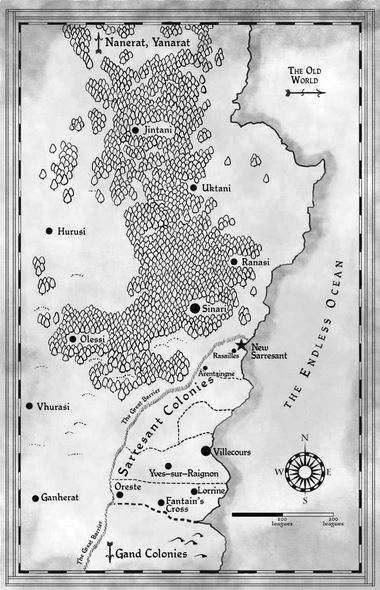

All of that is to explain why this month, I had to get a little creative when it came to keeping with the theme. I’m going to look at Soul of the World, the first book in the Ascension Cycle, an epic fantasy series by David Mealing. The world is inspired by the European settlement of North America. On the coastline are the colonies of Sarresant, including the capital city of New Sarresant, whose culture is reminiscent of France. To the south are the colonies of Gand, reminiscent of England. To the west of the colonies is the Great Barrier, which separates them from tribes indigenous to the land, among them the Sinari, from which one of the protagonist hails.

All of that is to explain why this month, I had to get a little creative when it came to keeping with the theme. I’m going to look at Soul of the World, the first book in the Ascension Cycle, an epic fantasy series by David Mealing. The world is inspired by the European settlement of North America. On the coastline are the colonies of Sarresant, including the capital city of New Sarresant, whose culture is reminiscent of France. To the south are the colonies of Gand, reminiscent of England. To the west of the colonies is the Great Barrier, which separates them from tribes indigenous to the land, among them the Sinari, from which one of the protagonist hails.

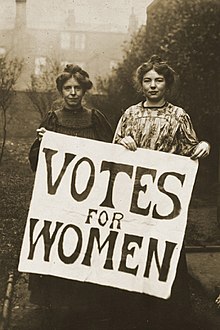

ideology has shifted over time. In the so-called “first wave” of feminism in the nineteenth century, for example, the general focus was on voting rights. During the middle of the twentieth century, many feminists fought for equal pay, while others protested against exploitation. At the transition to the twenty-first century, the focus for several years has included digital activism and collaboration, while other feminists focus on obtaining better representation in politics or family leave in the workplace. Just because someone puts their emphasis on one area of gender-based equity doesn’t mean they’re not “doing” feminism correctly. Many textbooks on the matter pluralize the word “feminism” to emphasize its plurality of meaning.

ideology has shifted over time. In the so-called “first wave” of feminism in the nineteenth century, for example, the general focus was on voting rights. During the middle of the twentieth century, many feminists fought for equal pay, while others protested against exploitation. At the transition to the twenty-first century, the focus for several years has included digital activism and collaboration, while other feminists focus on obtaining better representation in politics or family leave in the workplace. Just because someone puts their emphasis on one area of gender-based equity doesn’t mean they’re not “doing” feminism correctly. Many textbooks on the matter pluralize the word “feminism” to emphasize its plurality of meaning.

few times have we seen a female one. We didn’t know what to expect. There was a nationwide gasp when the beautiful Theron transformed herself into the physicality of Wuornos through the help of make-up, but also through something more, a dark vulnerability.

few times have we seen a female one. We didn’t know what to expect. There was a nationwide gasp when the beautiful Theron transformed herself into the physicality of Wuornos through the help of make-up, but also through something more, a dark vulnerability.

members, but there is no definitive evidence to prove them. She married young to Ferenc Nàdasdy. Shortly before at age thirteen, she gave birth to a child most likely fathered by a male of a lower social class, possibly even a servant. It is no surprise that the child was sent away immediately after birth. Bathory was considered a beauty in her time and following the birth of her first child, got into line with social expectations and often capitalizing on them. If anything, she seemed to become acutely aware of appearances.

members, but there is no definitive evidence to prove them. She married young to Ferenc Nàdasdy. Shortly before at age thirteen, she gave birth to a child most likely fathered by a male of a lower social class, possibly even a servant. It is no surprise that the child was sent away immediately after birth. Bathory was considered a beauty in her time and following the birth of her first child, got into line with social expectations and often capitalizing on them. If anything, she seemed to become acutely aware of appearances.

The first volume opens in Gotham City in 1940 at a women’s professional baseball game, where the players are forced to wear masks to hide their identities to protect themselves from harassment. This isn’t an origin story. In this world, the Batwoman, AKA Kate Kane, has been active on the baseball field as well as in the streets fighting crime, even merging the two when a group of criminals attacks the crowd gathered at the stadium. When Amanda Waller offers her the chance to help end the war, Kate doesn’t hesitate because, as she says, “I want my life to have greater meaning”1 a meaning she can’t get on the home front. Whether that’s a character flaw or strength is left up to the reader.

The first volume opens in Gotham City in 1940 at a women’s professional baseball game, where the players are forced to wear masks to hide their identities to protect themselves from harassment. This isn’t an origin story. In this world, the Batwoman, AKA Kate Kane, has been active on the baseball field as well as in the streets fighting crime, even merging the two when a group of criminals attacks the crowd gathered at the stadium. When Amanda Waller offers her the chance to help end the war, Kate doesn’t hesitate because, as she says, “I want my life to have greater meaning”1 a meaning she can’t get on the home front. Whether that’s a character flaw or strength is left up to the reader. which identity is the true one? How does donning a costume and wearing a mask alter the original identity? In “What’s Behind the Mask? The Secret of Secret Identities,” Tom Morris discusses this dual nature, particularly in regards to Superman and Batman, and comes to the conclusion that “a duality has replaced a singularity, but with a new, fused unity.”3 In essence, a superhero character isn’t their secret identity at certain times and their heroic identity other times. They’re both simultaneously.

which identity is the true one? How does donning a costume and wearing a mask alter the original identity? In “What’s Behind the Mask? The Secret of Secret Identities,” Tom Morris discusses this dual nature, particularly in regards to Superman and Batman, and comes to the conclusion that “a duality has replaced a singularity, but with a new, fused unity.”3 In essence, a superhero character isn’t their secret identity at certain times and their heroic identity other times. They’re both simultaneously. soldiers brought back from the dead. All the heroines we’ve been introduced to so far are here, so there’s a lot going on in this climactic scene. Among the chaos, though, the Batwoman says to Stargirl, “Symbols and stories got power, sugar. Fairy tales and propaganda. It’s all in the story you tell. It’s all in the story you sell. . . . Write your own ending.”5 This brief, powerful moment confirms that we don’t have to wait around for change to find us. We have the power to change our story, and through that, we transform ourselves.

soldiers brought back from the dead. All the heroines we’ve been introduced to so far are here, so there’s a lot going on in this climactic scene. Among the chaos, though, the Batwoman says to Stargirl, “Symbols and stories got power, sugar. Fairy tales and propaganda. It’s all in the story you tell. It’s all in the story you sell. . . . Write your own ending.”5 This brief, powerful moment confirms that we don’t have to wait around for change to find us. We have the power to change our story, and through that, we transform ourselves.

about her is quite a story unto itself, but she’s become more than just that. She’s a figure of compassion, tragedy and encapsulates the destruction of the Native American peoples’ way of life at the hands of the Europeans. Pocahontas remains a noble figure even in the face of violence and hatred. Somehow she remains personally, above the fray. Her history is obscured by time, but the mythology of the part she played is simultaneously romantic, poetic yet voiceless. There is never a moment in the records that we “hear” Pocahontas speak. But she plays a big role in the awareness of two prominent colonists, John Smith and John Rolfe.

about her is quite a story unto itself, but she’s become more than just that. She’s a figure of compassion, tragedy and encapsulates the destruction of the Native American peoples’ way of life at the hands of the Europeans. Pocahontas remains a noble figure even in the face of violence and hatred. Somehow she remains personally, above the fray. Her history is obscured by time, but the mythology of the part she played is simultaneously romantic, poetic yet voiceless. There is never a moment in the records that we “hear” Pocahontas speak. But she plays a big role in the awareness of two prominent colonists, John Smith and John Rolfe. dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death.”

dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death.” disbelief over the Englishmen’s folly. While the relationship between the settlers and the Powhatans were shaky at best, Pocahontas, young and representing her people arrived with life saving food. She was the face of possibility between the two cultures. There were attempts to garner positive relationships. These often failed, mostly through cultural misunderstandings, external pressures and pure aggression. Nonetheless, Pocahontas was painted as a figure that stood outside of all this. Her gifts of food were seen as acts of kindness.

disbelief over the Englishmen’s folly. While the relationship between the settlers and the Powhatans were shaky at best, Pocahontas, young and representing her people arrived with life saving food. She was the face of possibility between the two cultures. There were attempts to garner positive relationships. These often failed, mostly through cultural misunderstandings, external pressures and pure aggression. Nonetheless, Pocahontas was painted as a figure that stood outside of all this. Her gifts of food were seen as acts of kindness. father as well as weapons, her previous kindness was easily forgotten. However, her father the Chief was not interested in a trade of any kind. So Pocahontas remained with the settlers, eventually becoming Christian, adopting an English name (Rebecca), marrying and having a son with the widower John Rolfe.

father as well as weapons, her previous kindness was easily forgotten. However, her father the Chief was not interested in a trade of any kind. So Pocahontas remained with the settlers, eventually becoming Christian, adopting an English name (Rebecca), marrying and having a son with the widower John Rolfe.